Introduction

The exhibition, Arte Ritrovata. Ritorni in Laguna. Cultural Heritage Recovered by the Carabinieri TPC Venice Unit, allows us to explore various episodes related to the recovery and restitution of cultural heritage. It highlights the commendable collaboration between the Carabinieri Command for the Protection of Cultural Heritage and various bodies of the Ministry of Culture. These organisations work diligently to identify, safeguard, and enhance works of art removed from national heritage, in this case with a special focus on the metropolitan area of Venice.

Organised by the Segretariato regionale per il Veneto of the Ministry of Culture in collaboration with the Direzione regionale Musei Veneto, the Soprintendenza Archeologia, belle arti e paesaggio per il Comune di Venezia e Laguna, and the Italian Institute of Technology, this exhibition illustrates various case studies related to art crimes. These cases range from forgery to illicit export and from clandestine excavation to fraud.

The exhibition highlights the significant efforts in recovery, restitution, and protection made by the Carabinieri TPC of the Venice Unit over the past few years. It also serves as an opportunity to understand the protection procedures implemented by the bodies of the Ministry of Culture in collaboration with the Unit, including the enhancement of the recovered cultural goods within their original contexts or state-owned museums.

Arte Ritrovata. Ritorni in Laguna. Cultural Heritage recovered by the Carabinieri TPC Venice Unit is a journey that underlines the dangers to cultural heritage, but, above all, the perseverance and dedication of those who tirelessly work to protect it, ensuring that it continues to inspire and enrich future generations.

Introduction

Theft in St. Mark's Basilica

Jacopo Sansovino, 1486-1570

Wooden inlays, mid-16th century

Wood, 117 x 155 cm

In the heart of Venice, the magnificent complex of St. Mark's Basilica concealed, until the second half of the twentieth century, a treasure within a treasure. The presbytery was, in fact, adorned with splendid wooden panels - the inlays that you can admire in the video. These panels were the result of the extraordinary creative genius of Jacopo Sansovino, who, at the time, served as the proto (chief architect) for St. Mark's Basilica. The intricate inlay work was executed by the skilled hands of the craftsmen Antonio de' Grandi and Nicolò Zorzi.

These originally consisted of eight panels with a fir bottom and a walnut frame, measuring approximately 117 x 155 cm. They were inlaid with strips of various woods, including oak, cypress, maple, ebony, plane tree, alder, beech, pear, rosewood, and apple tree. Each piece is a masterwork, attesting to the artist’s extraordinary craftsmanship that weaves precious woods into timeless images, telling stories of virtue and spirituality. These inlays, inserted into the back screens of the presbytery, featured depictions of the seven Virtues, symbols of faith in God and good governance, flanked by the two patron saints of Venice, San Teodoro and San Marco.

The Justice inlay, originally set on the back of the ‘Dogal Throne', was removed by Napoleon's troops in 1797. Since 1852, it has been on display in the Correr Museum collection.

In the 1950s, the presbytery of St. Mark's Basilica underwent a reorganisation aimed at making the area where sacred rites were carried out more visible to the faithful, anticipating liturgical norms that would later be defined by the Second Vatican Council. The wooden panels were then removed and stored for a long time in warehouses from where they were eventually removed by an unknown hand.

It is probable that the theft of the inlays occurred when, following the flood that hit Venice in 1966, the city found itself in a state of vulnerability that put the protection of the entire artistic heritage at risk: the precious wooden panels were stolen, and they were lost in the shadows. In the 1970s, the inlays depicting Faith and Fortitude were found by the director of the Diocesan Museum, who rearranged them there.

Of the remaining inlays, the trace was officially lost until recently, when the Carabinieri TPC Venice Unit became aware of a publication dedicated to the pieces, commissioned by a Roman antiquarian. Two inlays – the Divine Hope and San Teodoro – were apparently available for sale at the same dealer’s shop. The support of the Soprintendenza A.B.A.P. per il Comune di Venezia e Laguna and the Prosecutor's Office of St. Mark's Basilica boosted the Carabinieri's investigations eventually leading to the recovery of the two precious works. The story unravelled further when the Carabinieri identified two other inlays - Prudence and Temperance - jealously guarded in a Tuscan villa.

By tracing the artworks’ sales and the economic transactions, the Carabinieri discovered that the six inlays had been sold at auction in Florence, at a villa called ‘L'Imperialino’, back in 1969. The auction catalogues from the period revealed a well-orchestrated deception: the pieces, in fact, had been attributed to minor authors, rather than to the well-known Jacopo Sansovino. The ruse had thus effectively hindered the traceability of the stolen goods.

However, the commitment and perseverance of the Carabinieri TPC Venice Unit have borne fruit. Six inlays, an integral part of a unique artistic heritage, have been reunited in the Museum of St. Mark's Basilica since 2014. Their story, though, is not over yet, as the investigations continue into the two missing artworks: San Marco and Charity, which remain lost to this day.

Theft in St. Mark's Basilica

Discovering Forgeries of Paintings

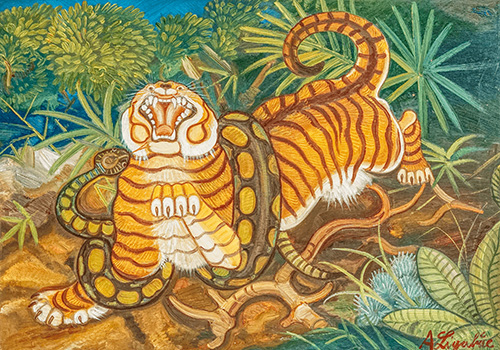

(Original: Antonio Ligabue (1899-1965), "Tiger with snake", Oil on faesite, 80 x 66 cm, “Antonio Ligabue” Archive Foundation, Parma)

Copy by unknown forger

Tiger with snake

Oil on canvas, 70 x 50 cm

The problem of fakes constitutes a significant challenge in the world of collecting and the art market. In addition to the historical, artistic, and economic implications, it is necessary to highlight how the Italian legal system addresses and penalises the crime of art forgery (Article 518-quaterdecies of the Italian Criminal Code).

But how do you recognise forgeries of paintings?

To ascertain the authenticity of a painting, it is essential to consider various aspects. First and foremost, prior to technical-scientific analyses, it is the stylistic and/or thematic anomalies and inconsistencies detectable through observation that serve as strong indicators for identifying a forgery. Sometimes, upon careful examination, these elements can be quite conspicuous, even to non-experts.

In this case, it is, in fact, the same distinctive characteristics of execution that reveal the painting as a falsely authenticated reproduction of Tiger with Snake, a twentieth-century artwork by the artist Antonio Ligabue (https://www.fondazionearchivioligabue.it/opere).

The work fully lacks the expressive power and emotional richness of the original, typical elements of Ligabue's pictorial language. The thick and heavy brushstrokes devoid of modulation and finesse of detail, the brown outline of the tiger, and the light colour palette - far from the brilliance and chromatic variety of the well-known original (which ranges from dark green to deep orange with blacks used to give depth and dynamism) - compose an image that, overall, is dull and distant from the explosive vitality that characterises Ligabue's painting. The difference is substantial in the colour rendering, the graphic precision of the flourishing vegetation, and the anatomical details of the animals, which constitute the original stylistic code and the heart of Ligabue's ‘naturalistic’ pictorial poetics.

Even the painter's signature shows clear signs of forgery; in particular, the Gothic upper strokes of the 'g' and 'a' are poorly reproduced. Furthermore, both the frame and the canvas appear too 'new' and 'clean' compared to the materials typically used by Ligabue for his oil paintings on canvas. Finally, the 'declaration of authenticity' on the back only superficially resembles the stylistic features found in authentic certificates by Sergio Negri. In fact, it lacks reference to the archive number relevant to this cataloguing, and the scholar's handwriting is crudely counterfeited, especially noticeable in the 'a,' 'b,' 'g,' and 'p' characters.

Beyond visual analysis, the thorough physico-chemical examination of the materials often presents a crucial tool for establishing the authenticity of a work of art. Indeed, artists employ specific pigments, binders, and supports that can be analysed and recognised through non-invasive or micro-invasive diagnostic investigations. These include infrared spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, or X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy, which allow the identification of elements and chemical compounds, or infrared reflectography and radiography, which highlight pentimenti, overpainting, modifications, and restorations.

There are many reasons that drive the forgery of artworks: a significant incentive is the economic value attributed to the creations of specific artists and the limited availability of original pieces in the market. In the case of Ligabue, whose production of oil paintings is relatively small but whose market value is quite high, some dealers have no qualms about offering fakes, enticing buyers to invest in a presumed 'bargain' due to prices lower than the value that originals would rightfully have. Sergio Negri himself stated that, over the years, he has encountered hundreds of forgeries of Ligabue’s works, executed both skilfully and crudely.

The market for counterfeit art is a widespread and continually evolving phenomenon.

The contribution of relevant authorities and specialised judicial police, such as the Carabinieri TPC, is essential to combat this practice. Seizures of counterfeits have reached significant figures in recent years, highlighting the extent of the problem. However, fighting the circulation of fakes requires constant vigilance and intense cooperation among experts, institutions, and buyers.

Discovering Forgeries of Paintings

Compulsory Acquisition by the State

Giandomenico Tiepolo, 1727-1804

Holy Family, 1770-1780 ca.

Oil on canvas, 38 x 45 cm

The artwork here displayed has been the protagonist of a complex series of events that have highlighted not only the importance of cooperation among different institutional actors responsible for the protection of artistic assets but also the strategic role of certain legal tools provided by Italian regulations for the safeguarding of cultural heritage, such as the State's power of pre-emption (compulsory acquisition).

Thanks to the skilled investigative work carried out by the Carabinieri TPC Venice Unit under the guidance of the local Public Prosecutor's Office, the painting, found hidden in an attic, was seized in Padua during a search following fraudulent bankruptcy.

In April 2022, one year after the restitution to the bankruptcy trustee, he presented the canvas to the Export Office of Milan for the issuance of the Certificate of Free Movement (Art. 68, Legislative Decree n. 42/2004), declaring it to be an authentic painting by Giandomenico Tiepolo. The Export Offices are the bodies of the Ministry of Culture responsible for controlling the circulation of works of art entering and leaving Italian territory, while the Certificate of Free Movement is the document that allows the definitive export of a cultural asset from the borders of the State, often in anticipation of a future sale to a foreign buyer.

The sequence of events, then, took an unexpected turn when the Export Office suspended the proceedings to carry out further investigations, also in collaboration with the Soprintendenza A.B.A.P. per il Comune di Venezia e Laguna. Deemed worthy of protection by the Advisory Commission of the General Directorate of Archaeology, Fine Arts, and Landscape, and denied the release of the Certificate of Free Circulation, the painting was finally evaluated by the Technical-Scientific Committee for the Fine Arts, which proposed its acquisition.

The procedure known as compulsory acquisition was activated. This is a legal measure governed by Article 70 of Legislative Decree n. 42/2004, the Code of the Cultural and Landscape Heritage. It is conceived to allow entry into public collections of artworks that have been presented to the Export Offices for definitive exit from Italy and are deemed to possess notable historical and artistic value, as well as being of interest to state or public museum collections.

In fact, the legislation provides that if a work of art is presented to obtain the certificate of free circulation for definitive export from Italian territory, the competent Export Office has the right to deny issuing the certificate and initiate the process of declaring the property to be of cultural interest. This would result in the property being retained within the national territory or suspending its release for proposing a direct purchase to the specific MiC General Directorate at a price corresponding to the value declared by the owner in the initial declaration.

The careful application of the compulsory acquisition procedure has guaranteed the protection and purchase of this masterpiece for the public heritage. Thanks to the timely actions of the authorities, the work has found a new and illustrious home in the Galleria Giorgio Franchetti alla Ca’ d’Oro, which boasts a collection of artworks from eighteenth-century Venice.

Compulsory Acquisition by the State

An International Journey

Jasper Geerards, c. 1620-1649/54

Still Life with Nautilus Shell, Lemons, Ham, and Chalice

Oil on panel, 59 x 74 cm

The legal case that revolves around this painting began within the walls of a prestigious Venetian palace in June 1999, when a Dutch antique dealer, already the owner of the artwork, became the victim of a cunning scam. Like many other Italian and foreign antiquarian colleagues, he had entrusted several works of art to a group of alleged mediators with the aim of organising an exhibition with the associated auction. However, he soon realised that he had been deceived: the painting, like the other artworks, had been stolen and the payment guarantees received were discovered to be null. The first investigations by the Carabinieri TPC Venice Unit led to the identification of the culprits of the scam and the clarification of their criminal responsibilities, but the precious painting by Jasper Geerards was yet to be found, and the antique dealer received compensation from the insurance he had taken out on the work.

However, the authorities did not cease their pursuit of the painting. It is in these circumstances that we can appreciate the significance of the database of illicitly removed cultural assets managed by the Carabinieri TPC. This crucial technological tool, mandated by the Code of the Cultural and Landscape Heritage (Art. 85, Legislative Decree n. 42/2004) and initially established in paper format in 1980, stands as the largest database on the topic, globally. It boasts over 8 million catalogued assets, encompassing approximately 1.3 million artworks still to be recovered. Thanks to this invaluable resource, in June 2018, the Carabinieri TPC Venice Unit successfully located Jasper Geerards' painting, which was up for sale at an auction house in Germany.

According to the Code of the Cultural and Landscape Heritage, works of art created more than 70 years ago by authors who are no longer living, and which have a value exceeding 13,500 euros, cannot leave the national territory without specific authorisation from the Ministry of Culture. The unauthorised export of such goods constitutes the crime of 'Illicit Exit or Export of Cultural Goods' (as per art. 518-undecies of the Italian Criminal Code).

After the painting was identified at an auction in Germany, the Carabinieri TPC Venice Unit continued the investigations, confirming the illicit export of the artwork from Italian territory. Following an international letter rogatory, it became possible to identify both the person responsible for transporting the painting to Germany and the instigator of the auction at the German auction house.

While investigations were underway, the unsold painting returned to Italy and was once again presented at an auction in Lombardy. Finally, in December 2021, the Carabinieri TPC Venice Unit managed to track down the artwork and recover it. They proceeded with its seizure and initiated a new investigative phase, coordinated by the Public Prosecutor's Office of Brescia.

The investigation focused on the various changes in ownership of the painting over time. After the scam in Venice, the artwork had been stolen and embarked on a significant journey through various Italian regions and abroad.

Thanks to the collaboration of art historians, officials from the Soprintendenza A.B.A.P. per il Comune di Venezia e Laguna and the Carabinieri TPC Venice Unit, further historical and artistic analyses and material observations were conducted to ensure the accurate identification of the painting. In particular, Superintendency officials played a crucial role in comparing the painting seized in 2021 with the work that disappeared in 1999, the item of the scam.

Concluding the investigations in February 2022, the Court of Brescia ordered the confiscation of the painting, definitively transferring it to the Ministry of Culture. The Ministry, in turn, designated the Palazzo Grimani Museum as the most suitable location for its display. This event marks the conclusion of a complex legal affair filled with explosive elements: a well-orchestrated scam, a missing artwork, illicit exports, and an intricate web of investigations by the Carabinieri TPC. The absence of other works by the Flemish painter in the Italian museum landscape makes this acquisition even more significant.

An International Journey

The Recovered Heritage of Ancient Altinum

-

A. Funerary bloc with carved lions

1st century CE

Aurisina limestone, 49 x 41 x 30 cm -

B. Funerary aedicula with portrait of a couple

1st century CE

Aurisina limestone, 85 x 73 x 18 cm

The finds showcased through the 3D animations are just two examples of the multitude of funerary monuments that lined the sides of the roads leading to Altino, particularly along ancient Via Annia and Via Claudia Augusta. These areas, as customary in the Roman world, were characterised by necropolises and served as a public display of the town's families' status.

Alongside the simple underground pit tombs, the funerary monuments varied in shape and size, ranging from mausoleums to small aediculae, from steles to urns with figurative lids. Due to their prominent location, these monuments have always been particularly vulnerable to looting, either for the recovery of building materials or for the search for precious objects within the burials. In more recent centuries, damage caused by agricultural activities that affected the buried structures must also be considered.

It is therefore not surprising that both the objects here virtually exhibited were discovered by chance during work in the fields near the city.

We know for sure that the aedicula's discovery occurred at the end of the nineteenth century during the reclamation of the area commissioned by Giuseppe Maria Reali, who had purchased the ‘Tenimento di Altino’ in 1851. Following these operations, numerous archaeological finds emerged. As there was no law for the protection of antiquities in effect at the time, the objects formed a rich private collection that was kept in the family villa and later passed down to heirs. The aedicula here displayed immediately became part of this collection, even appearing among the 17 assets of particular importance that were bound as national cultural heritage as early as 1937.

However, between the 1950s and 1960s, the piece disappeared. Only in 2017, the year in which the entire collection was acquired by the State and entrusted to the National Museum and Archaeological Area of Altino, did the Carabinieri TPC Venice Unit find it – unfortunately in fragments – on the market. The male head and the lower portion of both figures are completely missing, having already been heavily damaged before their disappearance.

Instead, the identification and recovery of the stone base with the lions, later assigned to Altino’s Museum, is the result of the most recent investigative activity by the Carabinieri TPC Venice Unit during the Altino ritrovata operation in April 2023. This investigation started thanks to the report of the Soprintendenza A.B.A.P. per l'area metropolitana di Venezia e le province di Belluno, Padova e Treviso. The Carabinieri's investigations were able to confirm the absence of the documentation needed to demonstrate the legitimate ownership of the archaeological asset by the previous holder. However, the very owner, after reporting the object to the Superintendency, cooperated with the Carabinieri's investigations.

Following the scientific analysis conducted by the archaeological officials of the Superintendency and after consulting the database of illicitly stolen cultural property, the Carabinieri managed to confirm the stone's Altinian origin and trace its history through various ownership changes since its initial discovery, presumably at the beginning of the twentieth century, although after the enactment of the so-called 'Rosati Law’ (Law n. 364/1909).

Upon concluding the investigations, the Public Prosecutor's Office at the Court of Treviso decided to release the artefact from seizure and return it to the public. It was assigned to the Ministry of Culture, namely Altino’s Museum, which already housed artworks of a similar type and provenance.

The recovery of archaeological artefacts and their addition to the State's cultural heritage constitutes one of the primary objectives of the Carabinieri TPC Venice Unit. The restoration of cultural treasures to the public is an act that reintegrates the historical memory of peoples, mends the wounds of time, and reinforces identities.

The Recovered Heritage of Ancient Altinum

Purchase and Export

"Leagros Group" (attributed to)

Attic "black figure" amphora

Last quarter 6th century BCE

Pottery, h. 36.70 cm

The amphora on display was seized in September 2022 by the Carabinieri TPC Venice Unit as part of the international police operation Pandora VII (https://www.journalchc.com/2023/05/04/operazione-pandora-vii- 60-arrests-and-11,000-stolen-artworks-recovered-in-14-countries/). Strong suspicions regarding the legitimate origin of the work had arisen at the time of the request for the release of the Certificate of Free Circulation (Art. 68, Legislative Decree n. 42/2004), presented by the vase holder to the Venice Export Office. These doubts were then confirmed by the investigations coordinated by the Public Prosecutor's Office at the Court of Venice, which revealed the lack of documentation certifying the legitimate ownership of the archaeological asset. In fact, since 1909 (Law n. 364, Per l’antichità e le belle arti), Italian legislation on cultural heritage presumes the State's ownership of archaeological assets unless proof to the contrary is provided. This measure was adopted precisely to counter the unchallenged haemorrhage of national cultural heritage and the illicit trafficking of artefacts.

The Carabinieri TPC managed to trace the collecting history of our amphora, which was purchased by the latest owner at a London auction in 2016. Previously, the piece had belonged to a Belgian collection that was entrusted on deposit to the Royal Museum of Art and History of Brussels in 1935. The artwork’s route before that period is still shrouded in mystery. However, the excellent state of conservation of the amphora and its integrity suggest that it came from a funerary context and, given the collecting history, this context can probably be traced back to Italy. As known, the figurative pottery produced by the artisans of Athens was so appreciated by the Etruscans that these vases were exported in large quantities to their cities: they constituted indispensable symbols of prestige and found a place of honour as funerary objects. The Etruscan necropolises thus preserved thousands of Greek vases, mostly in good condition. A similar provenience is assumed for our amphora, which led the Ministry's experts to definitively confer the vase to the National Archaeological Museum of Adria. This town corresponds to an ancient Etruscan centre whose excavations led to the discovery of numerous fragments of other amphorae assigned to the so-called 'Leagros Group'.

The story of this amphora is an example of how clandestine excavations and consequent illicit transactions can obscure the origins of a cultural asset, preventing its provenience from being established with certainty in the absence of valid attestation of its past.

Accurate pertaining documentation should be essential for the purpose of any sale. Certificates of authenticity and proof of legitimate ownership, in compliance with international regulations, make it possible to trace the origin of archaeological artworks, thus promoting the protection of cultural heritage and helping guarantee their lawful provenance.

The art market, however, is polluted by a large number of goods of dubious or unknown origin. Thefts and clandestine excavations deprive the communities of fragments of their own history, fuelling the circulation of works illegally transferred across borders.

Against this background, joint efforts and the international collaboration between law enforcement agencies, museums, cultural institutions, and non-governmental agencies are fundamental to ensure the recovery and restitution of stolen and looted assets and to protect cultural heritage worldwide thanks to the enforcement of framework agreements, starting with the well-known UNESCO Convention of 1970.

Purchase and Export

The Recovered Archaeological Collection

(Archaeological finds of different origins, from a private collection)

This partially displayed private collection originated during the 1970s with a core of 39 finds and subsequently expanded to reach 226 items. In 1999, it was declared of notable historical, artistic, and archaeological interest by the then Archaeological Superintendency for the Veneto region. Over time, the items have passed from hand to hand within the family, who have always mistakenly considered them personal assets. Unfortunately, most of these objects lack any evidence of provenance, and numerous pieces have recently been found to be fake.

In 2022, the entire collection underwent inspection by the Soprintendenza Archeologia, belle arti e paesaggio per il Comune di Venezia e Laguna. Evident critical issues emerged regarding the origin and ownership of the objects, leading to the seizure of the collection by the Carabinieri TPC Venice Unit in November of the same year. Judicial police and officials from the Ministry of Culture were able to proceed with the investigation with the full cooperation of the latest owner.

The investigations, coordinated by the Public Prosecutor's Office at the Court of Venice, confirmed the absence of documentation certifying the legitimate ownership of the artefacts by the current heir. Eventually, the Venice Prosecutor's Office decreed the release of the collection from seizure and assigned it to the Soprintendenza Archeologia, belle arti e paesaggio per il Comune di Venezia e Laguna.

Today, thanks to the joint efforts of the Carabinieri TPC Venice Unit and the A.B.A.P. Superintendency, these archaeological finds regain their historical and cultural significance, revealing to the public the essence of our past.

The Recovered Archaeological Collection